But, as there are degrees of Vows, so there are degrees of Punishments for Vows, there are solemn Matrimonial Vows, such as contract and are the most effectual Marriage, and have the most reason to be so; there are a thousand Vows and Friendships, that pass between Man and Man, on a thousand Occasions; but there is another Vow, call’d a Sacred Vow, made to God only; and, by which, we oblige our selves eternally to serve him with all Chastity and Devotion: This Vow is only taken, and made, by those that enter into Holy Orders, and, of all broken Vows, these are those, that receive the most severe and notorious Revenges of God; and I am almost certain, there is not one Example to be produc’d in the World, where Perjuries of this nature have past unpunish’d, nay, that have not been persu’d with the greatest and most rigorous of Punishments. I could my self, of my own knowledge, give an hundred Examples of the fatal Consequences of the Violation of Sacred Vows; and who ever make it their business, and are curious in the search of such Misfortunes, shall find, as I say, that they never go unregarded.

The young Beauty therefore, who dedicates her self to Heaven, and weds her self for ever to the service of God, ought, first, very well to consider the Self-denial she is going to put upon her youth, her fickle faithless deceiving Youth, of one Opinion to day, and of another to morrow; like Flowers, which never remain in one state or fashion, but bud to day, and blow by insensible degrees, and decay as imperceptibly. The Resolution, we promise, and believe we shall maintain, is not in our power, and nothing is so deceitful as human Hearts.

Written late in 1688 but not published until the early part of 1689, Aphra Behn’s The History Of The Nun: or, The Fair Vow-Breaker is an unexpected piece of short fiction in several ways. Most immediately, the text carries another of Aphra’s rather curious dedications, this one to Hortense Mancini, Duchesse Mazarin, whose history had long been intertwined with that of the Stuarts. Charles had actually proposed to her (or rather, for her) during his exile, but was rejected, the lady’s family seeing then no prospect of his restoration. Hortense was eventually married off to Armand de la Meilleraye, one of the wealthiest men in Europe, who was then created Duc Marazin. The marriage was bitterly unhappy due to the Duc’s numerous peculiarities and Hortense’s reckless disregard of convention.

Eventually Hortense fled both her husband and her country, finding a protector first in Louis XIV before being given a place at the English court while officially visiting her cousin, Mary of Modena. Ironically, she ended up as Charles’s mistress, effectively supplanting the much-despised Duchess of Portsmouth, but herself fell out of favour when she refused to curb her reckless behaviour. Hortense was bisexual, often cross-dressed, and had numerous affairs with people of both sexes—including the Duchess of Sussex, one of Charles’s illegitimate daughters. It was not this, however, but her affair with Louis I of Monaco that caused Charles to end their relationship. The two nevertheless remained friends, and first Charles and then James continued to support her. Remarkably, Hortense held onto her place at court even after the arrival of William and Mary, albeit on a reduced pension. During this time she established a salon which attracted many intellectuals, artists and writers, and gained a reputation as a patron of the arts.

The dedication to Hortense that precedes The History Of The Nun is fulsome enough to have caused some academics to ponder a possible relationship between the two women; Aphra herself being often been read as bisexual:

I assure you, Madam, there is neither Compliment nor Poetry, in this humble Declaration, but a Truth, which has cost me a great deal of Inquietude, for that Fortune has not set me in such a Station, as might justifie my Pretence to the honour and satisfaction of being ever near Your Grace, to view eternally that lovely Person, and hear that surprizing Wit; what can be more grateful to a Heart, than so great, and so agreeable, an Entertainment? And how few Objects are there, that can render it so entire a Pleasure, as at once to hear you speak, and to look upon your Beauty? A Beauty that is heighten’d, if possible, with an air of Negligence, in Dress, wholly Charming, as if your Beauty disdain’d those little Arts of your Sex, whose Nicety alone is their greatest Charm, while yours, Madam, even without the Assistance of your exalted Birth, begets an Awe and Reverence in all that do approach you, and every one is proud, and pleas’d, in paying you Homage their several ways, according to their Capacities and Talents; mine, Madam, can only be exprest by my Pen, which would be infinitely honour’d, in being permitted to celebrate your great Name for ever…

However, I see in this dedication something more significant, if not quite so titillating: Aphra Behn’s belated abandonment of the Stuarts—or at least, her abandonment of the hope clung to for so many years, that she would be recognised by them for her talent and her loyalty. William of Orange did not arrive in England until November 1688, and James did not abdicate (if we can agree to call it that) until December, yet here in a work licensed in October we find Aphra striving to attract the attention of a potential new patron. Of course, we can never know if she might have succeeded at long last in winning the financial support she so desperately needed, since by the time The History Of The Nun was published, Aphra was dying.

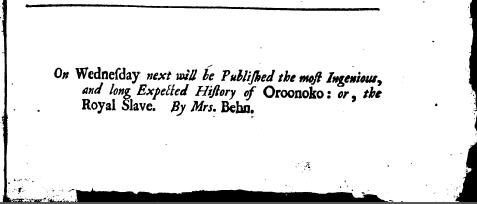

Another interesting thing about The History Of The Nun is Aphra’s use of the word “history”, which to this point has been employed deliberately to indicate, if not a true story, at least a story founded on truth: we have seen it used so in the omnibus Three Histories, which collects Oroonoko, The Fair Jilt and Agnes de Castro, short fictions which all contain a demonstrable measure of historical fact. The History Of The Nun conforms to this convention inasmuch as the dedication concludes with the assertion, The Story is true, as it is on the Records of the Town, where it was transacted; but as far as I am aware, no equivalent “true story” has been identified. Nor does The History Of The Nun contain any professions of being an eyewitness account, or even of having been told to Aphra. While the short opening section in which Aphra ruminates on the consequences of broken vows is written in the first person, when the story proper begins, the narrative voice switches to the third person. The only “personal” detail in The History Of The Nun comes near the beginning—a remark which may or may not be true, but which doubtless has added fuel to the fire of the long-running academic argument over whether or not Aphra was Catholic:

I once was design’d an humble Votary in the House of Devotion, but fancying my self not endu’d with an obstinacy of Mind, great enough to secure me from the Efforts and Vanities of the World, I rather chose to deny my self that Content I could not certainly promise my self, than to languish (as I have seen some do) in a certain Affliction; tho’ possibly, since, I have sufficiently bewailed that mistaken and inconsiderate Approbation and Preference of the false ungrateful World, (full of nothing but Nonsense, Noise, false Notions, and Contradiction) before the Innocence and Quiet of a Cloyster; nevertheless, I could wish, for the prevention of abundance of Mischiefs and Miseries, that Nunneries and Marriages were not to be enter’d into, ’till the Maid, so destin’d, were of a mature Age to make her own Choice; and that Parents would not make use of their justly assum’d Authority to compel their Children, neither to the one or the other; but since I cannot alter Custom, nor shall ever be allow’d to make new Laws, or rectify the old ones, I must leave the Young Nuns inclos’d to their best Endeavours, of making a Virtue of Necessity; and the young Wives, to make the best of a bad Market.

Amongst a certain school of literary scholars, Aphra Behn has a quite unfounded reputation as an author of “amatory fiction”: a categorisation often used to legitimise her dismissal from the timeline of the English novel. It gives me a certain evil pleasure to envisage the profound disappointment of those individuals when, upon perusing The History Of The Nun: or, The Fair Vow-Breaker – which, I grant you, is a title that seems to indicate salacious goings-on – they discovered it to be, not an account of wickedness behind convent walls, but an ironic tale of a woman so desperate to maintain her reputation for respectability, she eventually resorts to murder. Furthermore, as this previous quote indicates, The History Of The Nun is also a rather wry rumination upon the distance between the image of the ideal woman as envisaged by society, and the flawed reality stemming from a very human nature.

The anti-heroine of The History Of The Nun is Isabella, daughter of a Spanish nobleman. When his wife dies, the Count de Vallary is so grief-stricken that he decides to retire from the world by entering a monastery; resolving too that when she is old enough, Isabella will take the veil. The count’s sister is abbess of a convent: he bequeaths half his fortune to her in trust for Isabella, making clear his preference that his daughter should become a nun, but instructing that should she show a preference for the world, she should be permitted to marry and properly dowered.

At the age of only two, therefore, Isabella is taken into the convent to be raised amongst the nuns, proving as she grows to be as virtuous and accomplished as she is beautiful. She is, in fact, regarded as something of a prodigy:

…so that at the Age of eight or nine Years, she was thought fit to receive and entertain all the great Men and Ladies, and the Strangers of any Nation, at the Grate; and that with so admirable a Grace, so quick and piercing a Wit, and so delightful and sweet a Conversation, that she became the whole Discourse of the Town, and Strangers spread her Fame, as prodigious, throughout the Christian World; for Strangers came daily to hear her talk, and sing, and play, and to admire her Beauty; and Ladies brought their Children, to shame ’em into good Fashion and Manners, with looking on the lovely young Isabella.

Isabella’s aunt, meanwhile, is caught between her own desire to see Isabella become a nun, both for the fame and credit of the convent and for the sake of her fortune, and her promise to her brother. She fulfils the latter by speaking to her niece of the pleasures of the world and what her fortune can bring her, and by allowing her occasionally to go out in public with fashionable relatives. Isabella’s emergence from the convent, her reputation preceding her, sets the town of Iper in an uproar:

Isabella arriving at her Thirteenth Year of Age, and being pretty tall of Stature, with the finest Shape that Fancy can create, with all the Adornment of a perfect brown-hair’d Beauty, Eyes black and lovely, Complexion fair; to a Miracle, all her Features of the rarest proportion, the Mouth red, the Teeth white, and a thousand Graces in her Meen and Air; she came no sooner abroad, but she had a thousand Persons fighting for love of her; the Reputation her Wit had acquir’d, got her Adorers without seeing her, but when they saw her, they found themselves conquer’d and undone; all were glad she was come into the World, of whom they had heard so much, and all the Youth of the Town dress’d only for Isabella de Vallary, that rose like a new Star that Eclips’d all the rest, and which set the World a-gazing. Some hop’d, and some despair’d, but all lov’d… And now it was, that, young as she was, her Conduct and Discretion appear’d equal to her Wit and Beauty, and she encreas’d daily in Reputation, insomuch, that the Parents of abundance of young Noble Men, made it their business to endeavour to marry their Sons to so admirable and noble a Maid, and one, whose Virtues were the Discourse of all the World…

In spite of all this adulation, however, Isabella sees nothing in the world that draws her to choose it over a life of religious retreat, and nor do the conscientious counterarguments of her father and aunt, who urge the advantages of one and the disadvantages of the other upon her, have any effect upon her resolution. Seeing her determined, they withdraw all opposition; the Count de Vallary, indeed, then admits that he would have been very unhappy had she done anything else.

To one person above all others, Isabella’s resolution is a shattering disappointment: a young nobleman called Villenoys has fallen desperately in love with her, and done everything he can think of to persuade her to change her mind. His persistence lures Isabella into a correspondence, but although she pities the young man, her letters only reiterate her decision and urge him to seek his reward in the world. As the time for Isabella to take the veil draws near, Villenoys collapses in a dangerous fever. His despairing relatives plead with Isabella to relent and save his life. Her response is not quite what they hoped:

She believ’d, it was for her Sins of Curiosity, and going beyond the Walls of the Monastery, to wander after the Vanities of the foolish World, that had occasion’d this Misfortune to the young Count of Villenoys, and she would put a severe Penance on her Body, for the Mischiefs her Eyes had done him; she fears she might, by something in her looks, have intic’d his Heart, for she own’d she saw him, with wonder at his Beauty, and much more she admir’d him, when she found the Beauties of his Mind; she confess’d, she had given him hope, by answering his Letters; and that when she found her Heart grow a little more than usually tender, when she thought on him, she believ’d it a Crime, that ought to be check’d by a Virtue, such as she pretended to profess, and hop’d she should ever carry to her Grave; and she desired his Relations to implore him, in her Name, to rest contented, in knowing he was the first, and should be the last, that should ever make an impression on her Heart…

Small beer as this is, it serves to check Villenoys’ decline; though his family keep Isabella’s assumption of the veil from him until he is strong enough to hear the news. He then rejoins the military career from which he was diverted.

Isabella, meanwhile, gives no-one reason to suppose she repents her choice of a religious life. For two years she devotes herself to the demands of her order:

…there was never seen any one, who led so Austere and Pious a Life, as this young Votress; she was a Saint in the Chapel, and an Angel at the Grate: She there laid by all her severe Looks, and mortify’d Discourse, and being at perfect peace and tranquility within, she was outwardly all gay, sprightly, and entertaining, being satisfy’d, no Sights, no Freedoms, could give any temptations to worldly desires… But however Diverting she was at the Grate, she was most exemplary Devout in the Cloister, doing more Penance, and imposing a more rigid Severity and Task on her self, than was requir’d, giving such rare Examples to all the Nuns that were less Devout, that her Life was a Proverb, and a President, and when they would express a very Holy Woman indeed, they would say, “She was a very ISABELLA.”

Isabella’s close friend within the convent is Sister Katteriena, whose brother, Bernardo Henault, visits her regularly—and who as a matter of course sees much of Isabella. And suddenly, the serenely devoted Isabella finds herself confronted by a temptation of which previously she had no conception…

Katteriena is quick enough to discover what ails her friend, and confesses that her own presence in the convent is due to her enraged father discovering a secret passion between herself and a young man of lower social standing. Isabella begs her friend to tell her how she can regain mastery over herself, since for the first time in her life her thoughts and feelings are not under her control:

“Alas! (reply’d Katteriena) tho’ there’s but one Disease, there’s many Remedies: They say, possession’s one, but that to me seems a Riddle; Absence, they say, another, and that was mine; for Arnaldo having by chance lost one of my Billets, discover’d the Amour, and was sent to travel, and my self forc’d into this Monastery, where at last, Time convinc’d me, I had lov’d below my Quality, and that sham’d me into Holy Orders.” “And is it a Disease, (reply’d Isabella) that People often recover?” “Most frequently, (said Katteriena) and yet some dye of the Disease, but very rarely.” “Nay then, (said Isabella) I fear, you will find me one of these Martyrs; for I have already oppos’d it with the most severe Devotion in the World: But all my Prayers are vain, your lovely Brother persues me into the greatest Solitude; he meets me at my very Midnight Devotions, and interrupts my Prayers; he gives me a thousand Thoughts, that ought not to enter into a Soul dedicated to Heaven; he ruins all the Glory I have achiev’d, even above my Sex, for Piety of Life, and the Observation of all Virtues. Oh Katteriena! he has a Power in his Eyes, that transcends all the World besides: And, to shew the weakness of Human Nature, and how vain all our Boastings are, he has done that in one fatal Hour, that the persuasions of all my Relations and Friends, Glory, Honour, Pleasure, and all that can tempt, could not perform in Years…”

And here, of course, we find Aphra Behn’s underlying point that the dangers of forcing life-changing decisions upon girls too young and too inexperienced to understand themselves or what temptations the world might hold. Note, however, that Isabella’s trial has a double face. Most obviously she is frightened that her passion for Henault is coming between herself and God, tempting her to forsake her holy vows. Yet beyond that, even at these very earliest moments, is Isabella’s painful consciousness that what is at stake is not just her private dedication to God, but her public reputation: The Glory I have achiev’d, even above my Sex, for Piety of Life, and the Observation of all Virtues…

Isabella struggles against her passion for Henault; but not all the prayers and mortifications she puts herself through have the slightest effect. The death-blow to her hopes of conquering herself is delivered when she succumbs to temptation to the point of creeping near the grate to see Henault and listen to his conversation with Katteriena: she hears not only her friend’s angry scolding of her brother for daring to suppose that anyone as saintly and immaculate as Isabella could give a thought to earthly passion, but, fatally, Henault’s returning declaration of love and his plea that Katteriena do what she can to turn Isabella thoughts towards him. Knowing that she is loved gives Isabella power over herself—not to banish her forbidden passion, but to hide it from Katteriena; the saintly young woman teaches herself to dissemble and prevaricate, and succeeds in deceiving her friend. Believing she speaks for Isabella, Katteriena continues to scold and shame her brother for his wish to lure a nun from her vows; warning him that, even should he succeed, their father would consider it a blight upon the family honour and doubtless disinherit him.

Finding Katteriena opposed to him, Henault also begins to dissemble, convincing his sister that her arguments have swayed him. Both he and Isabella resume their previous behaviours—until one day, during Henault’s visit to the grate, he and Isabella find an opportunity for private conversation. Their mutual declaration leaves Isabella more bewildered and enflamed than ever, and she spends a sleepless night devoted to the age-old art of sophistry:

She had try’d Fasting long, Praying fervently, rigid Penances and Pains, severe Disciplines, all the Mortification, almost to the destruction of Life it self, to conquer the unruly Flame; but still it burnt and rag’d but the more; so, at last, she was forc’d to permit that to conquer her, she could not conquer, and submitted to her Fate, as a thing destin’d her by Heaven it self; and after all this opposition, she fancy’d it was resisting even Divine Providence, to struggle any longer with her Heart; and this being her real Belief, she the more patiently gave way to all the Thoughts that pleas’d her… She…was resolv’d to conclude the Matter, between her Heart, and her Vow of Devotion, that Night, and she, having no more to determine, might end the Affair accordingly, the first opportunity she should have to speak to Henault, which was, to fly, and marry him; or, to remain for ever fix’d to her Vow of Chastity. This was the Debate; she brings Reason on both sides: Against the first, she sets the Shame of a Violated Vow, and considers, where she shall shew her Face after such an Action; to the Vow, she argues, that she was born in Sin, and could not live without it; that she was Human, and no Angel, and that, possibly, that Sin might be as soon forgiven, as another… Some times, she thought, it would be more Brave and Pious to dye, than to break her Vow; but she soon answer’d that, as false Arguing, for Self-Murder was the worst of Sins, and in the Deadly Number. She could, after such an Action, live to repent, and, of two Evils, she ought to chuse the least; she dreads to think, since she had so great a Reputation for Virtue and Piety, both in the Monastery, and in the World, what they both would say, when she should commit an Action so contrary to both these, she posest; but, after a whole Night’s Debate, Love was strongest, and gain’d the Victory…

But matters having come to a head, it is Henault who perceives the enormity of the step, and who hesitates – not least because he knows that he will indeed be disinherited. Isabella manages to convince him, however, although in terms that remind us that she is both young and inexperienced:

I thought of living in some loanly Cottage, far from the noise of crowded busie Cities, to walk with thee in Groves, and silent Shades, where I might hear no Voice but thine; and when we had been tir’d, to sit us done by some cool murmuring Rivulet, and be to each a World, my Monarch thou, and I thy Sovereign Queen, while Wreaths of Flowers shall crown our happy Heads, some fragrant Bank our Throne, and Heaven our Canopy: Thus we might laugh at Fortune…

Isabella’s reputation makes the elopement almost comically easy. For one thing, she is trusted with the keys to the convent; for another—

Isabella’s dead Mother had left Jewels, of the value of 2000l. to her Daughter, at her Decease, which Jewels were in the possession, now, of the Lady Abbess, and were upon Sale, to be added to the Revenue of the Monastery; and as Isabella was the most Prudent of her Sex, at least, had hitherto been so esteem’d, she was intrusted with all that was in possession of the Lady Abbess, and ’twas not difficult to make her self Mistress of all her own Jewels; as also, some 3 or 400l. in Gold, that was hoarded up in her Ladyship’s Cabinet, against any Accidents that might arrive to the Monastery; these Isabella also made her own…

Making their escape, the two flee the country. They are married, and take a farm near a small village under the assumed name of Beroone. They do not neglect to attempt to obtain a variety of pardons, but without much success: Henault is indeed disinherited; and although he adores Isabella, he has been raised in luxury, and the thought of future poverty begins to fret him. His worries are exacerbated by the continuous difficulties that beset him as he tries to make the farm a going concern—until he, like Isabella before him, becomes proverbial:

…so that it became a Proverb all over the all over the Country, if any ill Luck had arriv’d to any body, they would say, “They had Monsieur BEROONE’S Luck.”

However, Isabella manages to win pardon from her aunt and, in time, from the church authorities, which allows the two of them to return home. The Abbess gives them what financial assistance she can, but Henault’s father goes no further than promising to equip him if he will leave Isabella and enter the army; while various interested parties likewise argue that he should enter the service of his country as a step towards expiating his sin of inducing a nun to break her vows. Henault is finally won over, but the first consequence of his decision is tragedy: when she hears that he will be leaving her, Isabella collapses and miscarries. Henault remains with her another month, while she recovers, but then forces himself to go.

Once in the army, Henault finds himself stationed with a certain Villenoys, whose name he knows… In spite of, or because of, their mutual passion for Isabella, the two become fast friends. The two serve together—and it is Villenoys who must break to Isabella the news of her husband’s death…

Isabella’s tragedy has the effect of restoring her public reputation, forsaken upon her elopement:

She continu’d thus Mourning, and thus inclos’d, the space of a whole Year, never suffering the Visit of any Man, but of a near Relation; so that she acquir’d a Reputation, such as never any young Beauty had, for she was now but Nineteen, and her Face and Shape more excellent than ever; she daily increas’d in Beauty, which, joyn’d to her Exemplary Piety, Charity, and all other excellent Qualities, gain’d her a wonderous Fame, and begat an Awe and Reverence in all that heard of her, and there was no Man of any Quality, that did not Adore her. After her Year was up, she went to the Churches, but would never be seen any where else abroad, but that was enough to procure her a thousand Lovers; and some, who had the boldness to send her Letters, which, if she receiv’d, she gave no Answer to, and many she sent back unread and unseal’d: So that she would encourage none, tho’ their Quality was far beyond what she could hope; but she was resolv’d to marry no more, however her Fortune might require it.

Villenoys continues to visit Isabella, and his love for her reawakens. Though she admits his friendship, she resists his courtship for two years, until her aunt dies and with her Isabella’s slender financial support. Confronted by grim reality, Isabella contemplates re-entering a convent, but finally shies away from the idea: not only did she promise Henault she would not, but, Her Heart deceiv’d her once, and she durst not trust it again, whatever it promis’d. Realistically, her only option is to marry; and so she brings herself to listen to Villenoys—after the usual delusionary arguments, of course:

…’twas for Interest she married again, tho’ she lik’d the Person very well; and since she was forc’d to submit her self to be a second time a Wife, she thought, she could live better with Villenoys, than any other, since for him she ever had a great Esteem; and fancy’d the Hand of Heaven had pointed out her Destiny, which she could not avoid, without a Crime.

She manages to hold Villenoys off for another year, but finally the two are married; and as time passes, Isabella develops a genuine affection for her husband. In contrast to her struggles when married to Henault, Villenoys lavishes upon her all that money can buy, while Isabella dedicates herself to regaining the favour of heaven:

She had no Discontent, but because she was not bless’d with a Child; but she submits to the pleasure of Heaven, and endeavour’d, by her good Works, and her Charity, to make the Poor her Children, and was ever doing Acts of Virtue, to make the Proverb good, That more are the Children of the Barren, than the Fruitful Woman.

Villenoys is away from home on a hunting trip when Isabella receives a most unexpected visitor:

And pulling off a small Ring, with Isabella’s Name and Hair in it, he gave it Maria, who, shutting the Gate upon him, went in with the Ring; as soon as Isabella saw it, she was ready to swound on the Chair where she sate, and cry’d, Where had you this? Maria reply’d, An old rusty Fellow at the Gate gave it me, and desired, it might be his Pasport to you; I ask’d his Name, but he said, You knew him not, but he had great News to tell you. Isabella reply’d, (almost swounding again) Oh, Maria! I am ruin’d.

It is indeed Henault; a Henault with hair and beard long and wildly tangled, so worn down and prematurely aged, so ragged and thin, as to be almost unrecognisable. He tells Isabella that he was wounded almost to death, but saved by his captors, who recovered him for ransom. Writing several times to his father but getting no response, he was consequently sold into slavery, from which he finally managed to escape.

By this time Henault has had a chance to absorb the signs of wealth in Isabella’s home, and finds himself gripped by a terrible fear… Isabella, meanwhile, is gripped by some fears of her own:

Shame and Confusion fill’d her Soul, and she was not able to lift her Eyes up, to consider the Face of him, whose Voice she knew so perfectly well. In one moment, she run over a thousand Thoughts. She finds, by his Return, she is not only expos’d to all the Shame imaginable; to all the Upbraiding, on his part, when he shall know she is marry’d to another; but all the Fury and Rage of Villenoys, and the Scorn of the Town, who will look on her as an Adulteress: She sees Henault poor, and knew, she must fall from all the Glory and Tranquility she had for five happy Years triumph’d in…

However, she dissembles, speaking gently and welcomingly to Henault and leading him to a bedchamber—although she manages to put off being compelled to join him in bed, by pleading her usual evening prayers. This is so entirely in character that Henault’s suspicions are lulled; and, exhausted by his travails, he falls asleep before Isabella returns.

Prayers, indeed:

’Tis true, Isabella essay’d to Pray, but alas! it was in vain, she was distracted with a thousand Thoughts what to do, which the more she thought, the more it distracted her; she was a thousand times about to end her Life, and, at one stroke, rid her self of the Infamy, that, she saw, must inevitably fall upon her; but Nature was frail, and the Tempter strong: And after a thousand Convulsions, even worse than Death it self, she resolv’d upon the Murder of Henault, as the only means of removing all the obstacles to her future Happiness; she resolv’d on this, but after she had done so, she was seiz’d with so great Horror, that she imagin’d, if she perform’d it, she should run Mad; and yet, if she did not, she should be also Frantick, with the Shames and Miseries that would befal her; and believing the Murder the least Evil, since she could never live with him, she fix’d her Heart on that; and causing her self to be put immediately to Bed, in her own Bed, she made Maria go to hers, and when all was still, she softly rose, and taking a Candle with her, only in her Night-Gown and Slippers, she goes to the Bed of the Unfortunate Henault, with a Penknife in her hand; but considering, she knew not how to conceal the Blood, should she cut his Throat, she resolves to Strangle him, or Smother him with a Pillow; that last thought was no sooner borne, but put in Execution; and, as he soundly slept, she smother’d him without any Noise, or so much as his Struglin…

Barely has the deed been done, however, than Villenoys unexpectedly returns home. The distracted Isabella is almost overcome, but finally realises she has to tell him the truth—or at least some of it. She does tell him of Henault’s return, but convinces him that Henault died of the shock of hearing that she was married to Villenoys. Her hysterical pleading sways her adoring husband who, learning that only Maria knows of the visitor, and that she does not know his identity, makes a grim resolution: he will carry Henault’s body to a nearby bridge, and throw it into the river below, which will carry it to the sea. He is reassured by his own examination of the body that Henault has indeed changed so much that, even if discovered, he will not be identified. Villenoys redresses the body, ordering Isabella to fetch a sack and some needle and thread. She does so…

Isabella all this while said but little, but, fill’d with Thoughts all Black and Hellish, she ponder’d within, while the Fond and Passionate Villenoys was endeavouring to hide her Shame, and to make this an absolute Secret: She imagin’d, that could she live after a Deed so black, Villenoys would be eternal reproaching her, if not with his Tongue, at least with his Heart, and embolden’d by one Wickedness, she was the readier for another, and another of such a Nature, as has, in my Opinion, far less Excuse, than the first; but when Fate begins to afflict, she goes through stitch with her Black Work… When he had the Sack on his Back, and ready to go with it, she cry’d, Stay, my Dear, some of his Clothes hang out, which I will put in; and with that, taking the Pack-needle with the Thread, sew’d the Sack, with several strong Stitches, to the Collar of Villenoy’s Coat, without his perceiving it, and bid him go now; and when you come to the Bridge, (said she) and that you are throwing him over the Rail, (which is not above Breast high) be sure you give him a good swing…

Irony is the prevailing key-note of The History Of The Nun, in which, not actual piety, but the reputation for piety, becomes the motivation for murder. While it does operate as a commentary upon the sometimes unrealistic expectations placed upon “good” women, ultimately this short tale works best as an examination of a complicated psychology, with Isabella’s vision of herself as a model of purity and religious devotion driving her to unspeakable crimes. It is difficult to know what message, if any, Behn wanted the reader to take away from this perversely amusing horror story. Certainly it is difficult to believe that she intended it taken seriously as a warning against the perils of vow-breaking; although her early remarks upon the dangers of premature vow-taking, whether marital or religious, are evidently sincere.

In the end, it is hard to shake the feeling that Behn was so taken with the blackly comic aspects of her story, her message became obscured by its delivery. She even gives us what might be considered, at least from Isabella’s warped perspective, a happy ending: her crimes exposed, Isabella is tried, condemned and executed, and in the process wins a fame far beyond mere reputation—that of martyrdom:

…as soon as she was accus’d, she confess’d the whole Matter of Fact, and, without any Disorder, deliver’d her self in the Hands of Justice, as the Murderess of two Husbands (both belov’d) in one Night: The whole World stood amaz’d at this; who knew her Life a Holy and Charitable Life, and how dearly and well she had liv’d with her Husbands, and every one bewail’d her Misfortune, and she alone was the only Person, that was not afflicted for her self… While she was in Prison, she was always at Prayers, and very Chearful and Easie, distributing all she had amongst, and for the Use of, the Poor of the Town, especially to the Poor Widows; exhorting daily, the Young, and the Fair, that came perpetually to visit her, never to break a Vow: for that was first the Ruine of her, and she never since prosper’d, do whatever other good Deeds she could… She made a Speech of half an Hour long, so Eloquent, so admirable a warning to the Vow-Breakers, that it was as amazing to hear her, as it was to behold her… She was generally Lamented, and Honourably Bury’d.

In her dedication of The Lucky Mistake to “George Greenveil” (George Granville, Baron Lansdowne), published the year of her death, Aphra Behn comments:

In her dedication of The Lucky Mistake to “George Greenveil” (George Granville, Baron Lansdowne), published the year of her death, Aphra Behn comments: