“The man has arrived thus far. To-morrow, by his secret labours, his ideas will be promulgated, and he will find a powerful auxiliary in European politics. The man will then transform himself; in order to obtain access to crowned personages, he will become a mighty lord. He will amass into one mountainous heap the bitter and legitimate hatreds; all the crying wrongs committed by the insatiable cupidity, by the perfidious ambition, by the cowardly tyranny of his enemy. His voice, which will be heard, will preach the establishment of an immense crusade. Then this great lord will for a time throw off his golden honours, and his velvet robes, and become the Irishman, Fergus, in order to gain the hearts of his countrymen. He will revisit his poor Ireland; his treasures will be employed in relieving her indescribable distress, and his hand always open to bestow, will one day stretch toward the east, and will point to London in the distance, whence descends upon Erin, the torrent of her sufferings.

“And then he will repeat the death-cry of his father: Arise—and war to England.”

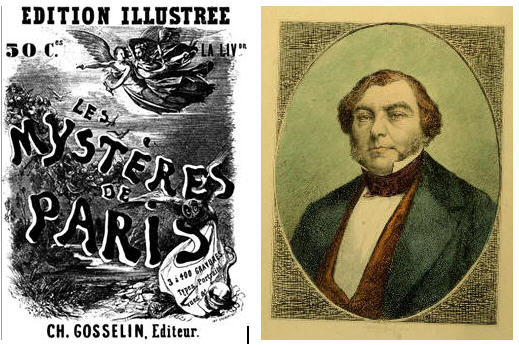

While the timing of the publication of G. W. M. Reynolds’ own sprawling penny-dreadful, The Mysteries Of London, was no doubt primarily responsible for the failure of Paul Féval’s Les Mystères de Londres to appear in English translation in 1844, it is not difficult to imagine that whatever enthusiasm there might have been for this French-penned crime drama in the wake of the enormous popularity of Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris, it was quenched by the realisation that for all of its many and varied crime plots and French criminal characters, the real Bad Guy in Les Mystères de Londres was England. Sue’s stringent criticisms of his own country, his own society, were one thing; a Frenchman depicting England as a monster of tyranny, oppression and injustice, both at home and across the world—particularly in a work aimed (at least overtly) at the working-classes—was something else entirely. And to make things even worse, the main thread of the narrative concerns a plot against England that is explicitly Catholic in nature.

But even as English readers gobbled up the myriad exciting improbabilities of Reynolds’ The Mysteries Of London and its follow-up, The Mysteries Of The Court Of London, a version of Les Mystères de Londres did finally creep out into the marketplace. Published in 1847, translated by one “R. Stephenson”, about whom I have been able to find no information, and bearing no hint of the identity of the work’s original author, The Mysteries Of London; or, Revelations Of The British Metropolis is a poor shadow of Paul Féval’s original work, a one-volume, 500-page rendering of his four volumes.

It is hardly to be wondered at that The Mysteries Of London is a difficult, unsatisfactory read. Like its model, Les Mystères de Paris, this is a rambling, undisciplined, multi-plotted story full of people with secret identities (sometimes several at once): one difficult enough to follow even without huge chunks of the narrative being excised. As it stands, it is frequently impossible to tell whether something is mysterious because Féval meant it to be mysterious, or because Stephenson hacked out the explanation—although it progressively becomes evident that the latter is responsible for a majority of the reader’s frustrations.

Allow me to offer a minor example of the editing style that plagues this work throughout: one of the novel’s heroines, a girl called Susannah, is steeling herself to tell her brief life-history to the man she loves, revealing that she is the daughter of Ishmael Spencer, “the forger”, “the robber” and (worst of all?) “the Jew”. She has just got through explaining that she was never allowed out of the house, and had no companions other than a maid, Temperance, and a disfigured manservant, Rehoboam:

“It was one evening. Ishmael had not for two days been in that part of the house in which I lived. I was in the parlour, where I had just fallen asleep with my head upon Cora’s shoulder. I raised my eyes; whether I was still sleeping or awake, I know not, but I saw a lady cautiously entering the parlour with Temperance. How beautiful that lady seemed to me, and how much goodness was there in her features!… Corah lay trembling under me, for Corah was timid also, and was alarmed at the appearance of a stranger…”

Thus, at a moment when we are no doubt supposed to be speculating about the identity of the “beautiful lady”, all I could think was, “Who the hell is Cora(h)!?” – to whom we will continue to get confusing references for quite a number of pages, until (more by accident than design, we suspect) Stephenson leaves in his text the key to the mystery, after Ishmael finds out about Susannah’s visitor:

“‘Do not sleep any more in the parlour, my child; and, when you have dreams as this, always come and tell me at once. Will you do so, Susannah?’ My father’s questions were always an order or a threat. I bowed my head and trembled. ‘Will you do what I tell you?’ repeated Ishmael, shaking me by the arm. ‘I will, sir.’ ‘Yes, Susannah? You are a good girl; and, besides, if you did not, I would kill your doe.'”

Ohhhhhhhhhh, she has a pet deer! In the middle of London. Which sleeps in the house with her. Of course she does.

This is, as I say, a very minor example of Stephenson’s editing style. More serious (and even more frustrating) is the eventual realisation that he also censored Féval’s text. What remain are mere allusions to shocking material that has been removed—enough to hint at what happened without us ever knowing the details. Two plot-threads in particular are affected by this. In one, we have an improbable love affair between Susannah, the daughter of Ishmael Spencer, and the aristocratic Brian de Lancaster, who is waging a personal and public war against his brother, the dissolute and criminal Earl of White Manor. It will, at great length, be revealed that (of course) Ishmael was not Susannah’s real father; that she is the daughter of Lord White Manor and his discarded wife (the mysterious, beautiful lady of Susannah’s vague childhood memories); and that Brian and Susannah are therefore uncle and niece. We are shown the aftermath of this devastating discovery—

Susannah has seen Brian de Lancaster but once since their fatal separation in Wimpole Street, and this was immediately after the decease of the Earl of White Manor, which took place during one of his terrible attacks at Denham Park. He came to inform her of the death of her father, and of his having succeeded to the peerage, and then set out again for London, without so much as sleeping one night under the same roof with Susannah.

—but not the moment of realisation.

Still more frustrating in its way is perhaps the most shocking of all this work’s shocking subplots, that involving the sisters, Clara and Anna Macfarlane, whose romantic affairs drive most of what we might call the “middle-layer” plots. One of the criminal gang, Bob Lantern, is offered money by two different people in return for the person of a beautiful young woman, and decides to cash in on both offers by abducting and selling the sisters. One of them, Anna as it turns out, is destined to be the unwilling plaything of the Earl of White Manor, although she is rescued before he gets around to having his way with her. Clara is not so fortunate, being sold to a certain Dr Moore to be the test subject in his experiments. Hints about this come and go, so that we are never sure of all she has been subjected to; but what remains is hair-raising enough:

For a time, the doctor ceased his experiments on Clara, who had become useless to him, and left her under the charge of Rowley, who divided his leisure moments between her and his Toxicological Amusements…

Rowley had been ordered to supply her with good food, that she might better be able to sustain the galvanic shock to which the doctor wished to expose her…

Clara Macfarlane was much changed. The traces of the long and cruel martyrdom she had been made to suffer, were clearly perceptible in her pallid and meagre face. Her form, so beautiful in its youthful proportions, had become debilitated and stooping… In the eyes of Clara, was some what of a wild expression. The horrible shock that had been given to her nervous system, had left behind it an affection [sic.?] which continually distorted her features by sudden and painful twitchings…

The final exasperation is that for some reason the text of The Mysteries Of London was rendered without any punctuation of the dialogue: I have inserted it in my quotes for ease of reading, but it isn’t present in the book itself. For example, the conversation quoted up above, between Ishmael and Susannah, is presented as follows:

Do not sleep any more in the parlour, my child; and, when you have dreams as this, always come and tell me at once. Will you do so, Susannah? My father’s questions were always an order or a threat. I bowed my head and trembled. Will you do what I tell you? repeated Ishmael, shaking me by the arm. I will, sir. Yes, Susannah? You are a good girl; and, besides, if you did not, I would kill your doe.

The cumulative result is a rather gruelling five hundred pages, in which we are never sure who anyone is, or who is speaking from moment to moment—or even if certain passages are meant to be dialogue at all. But if reading The Mysteries Of London was a chore rather than a pleasure, reviewing it is even more difficult: far more so than, say, dealing with the full six volumes of Les Mystères de Paris. In fact it can’t be done in any coherent way, except by, as it were, speaking backwards from the point at which the fragmented pieces fall into place.

Briefly, then, The Mysteries Of London has two main parallel plots, one dealing with machinations at the very highest levels of English society, the other with the activities of a brutal criminal gang; with most of the “nice” characters, like the Macfarlane sisters, caught between and swept up into danger because of one or the other (or both). The link between all the story’s threads is the Marquis de Rio Santo, aka “Mr Edward”, real name: Fergus O’Brian—the money and the genius behind a plot to lead the Irish in violent revolt against the English government, with his own part being to use his access to the highest levels of society to assassinate the British monarch (who at the time of the story’s setting was the relatively inoffensive William IV).

It is late in the narrative before we are finally let in on the life-history of this work’s anti-hero, but his story, when it finally emerges, is one of an amusing and spectacular climb up the social ladder; one which might reasonably open, “Once upon a time—x“. Some twenty years earlier, then, the lovely Mary Macfarlane fell in love with and became engaged to the poor Irishman Fergus O’Brian, rejecting the advances of Godfrey de Lancaster, afterwards the Earl of White Manor. A quarrel led to a duel in which de Lancaster was wounded; and Fergus, being a poor Irishman, was tried, convicted and transported to Australia. During his transportation, Fergus gained a friend and collaborator in the form of an angry Scot named Randal Graham; the two agree to (i) escape, (ii) turn pirate, and (iii) find some way to stick it to England:

Fergus O’Brian had not become a pirate, merely to be a pirate. He had other views besides that of making booty more or less abundant; and every action of his during the four years in which he had traversed those seas, was a stone added to the gigantic edifice, of which he was the architect.

It is not necessary to state, that his attacks were made on British ships, in preference to all others. They pillaged, sunk, or blew up, more ships belonging to the East India Company, than all the French privateers that ever swam…

Fergus also spends these years travelling the world, getting a good look at the brutality and exploitation that are the hallmarks of English colonisation and English trade, and gaining recruits to his cause:

Quitting the Indian seas, he only changed the scene, again to find, at intervals more distant from one another, the same hatred against England, still covered and restrained, but ready to burst forth. At the Cape of Good Hope, the Dutch boors—in America, both the Canadas, from one extremity to the other, groaning under the most horrible oppression, and venting their cries of distress, which were soon to find an echo in a French heart…

An amusing interlude follows, in which it is solemnly explained to us that Napoleon – who had, The most noble, the most enlightened, and the boldest mind, which has perhaps ever dazzled the world – escaped from St Helena with the single goal of crushing English tyranny…

…but since he didn’t quite manage it, it was up to Fergus O’Brian to pick up his slack.

During his travels, Fergus managed to be of service of John VI of Portugal, whose reward paved the way for Fergus’s great plan against England:

In 1822, one year after the restoration of the house of Braganza, Fergus O’Brian, the poor orphan from St Giles’s, was created a grandee of Portugal, of the first order, Grand Cross of the Order of Christ, and Marquis de Rio Santo in Paraiba. Fergus was also, by royal prescription, authorised to bear the name and title of a noble family which had become extinct, the Alacaons, of Coimbra.

So that when we heard announced in the proud drawing rooms of the Westend, the sounding titles of Don Jose Maria Telles de Alacaon, Marquis de Rio Santo, it was not the name of a vulgar adventurer, ennobled by the grace of fraud, and strutting about under a false title, but it was really a great nobleman, of legitimate manufacture, a marquis by royal grant, an exalted personage, upon whose breast glitterd the insignia of several of the most distinguished and most rarely bestowed European orders, which he had acquired and merited…

Perhaps the single most interesting thing about The Mysteries Of London is that its anti-hero is both a genuine aristocrat (albeit a created one) and a poor, dispossessed Irish revolutionary. His toggling between the various levels of society is, therefore, rather more convincing than usual: he is able both to command a dangerous and extensive criminal gang, and enter unhindered into the very highest circles of society. The latter, indeed, is why he takes upon himself the task of regicide: as the noble Marquis de Rio Santo, he has no trouble getting access to the king.

Paul Féval does not pull any punches with respect to English tyranny, dwelling angrily upon abuses in India, the opium trade in China, the brutalities of Botany Bay—but it is with respect to the treatment of Irish Catholics by English Protestants that he really lets himself go. And this is, of course, Fergus’s background, the first of many injustices suffered, with his respectable Irish family gradually stripped of their possessions and their savings by the cruel manoeuvring of English landlords, his sister seduced and abandoned, and his parents dying of grief and starvation:

He again threw himself upon his knees and endeavoured to pray. But a mysterious voice resounded in his ears, and repeated to him his father’s dying words:

“Arise! and war to England!”

He sprang to his feet; his brows were knit, and a purple tinge chased the paleness from his fine features, and flashed fire.

This was not—and no one could have been deceived by it—the transient anger of a child; it was the deadly hatred of a man. And in that poor room, in the poorest district of all London, arose a cloud, the precursor of a tempest, which might shake the three kingdoms to their foundations.

Fergus advanced with firm steps towards the bed, and then slowly drew from his forehead to his chest, and then from one shoulder to the other, the sacred sign of the Catholic religion.

“My father!” he exclaimed, with head erect and outstretched hand, “I here swear to obey you.”

And indeed, Fergus’s planned revenge is nothing less than the violent overthrow of the English government, for which purpose he spends years building a revolutionary army, predominantly but not exclusively Irish, which he has ferried to England as his plans move towards fruition. Féval allows Fergus’s schemes to progress so far as his army being in place around London, only waiting for their commander’s signal to strike—

—but of course that signal does not, cannot, come.

There is a strange split-vision about the conclusion of The Mysteries Of London. On one hand Féval is clearly enjoying his violently anti-English fantasy; but at the same time he has to find a way for the hitherto invincible Fergus to stumble at the last. His compromise is to have, not Fergus’s revolution fail, but his private crimes rise up against him. It is not the government or the army who stops Fergus, but two personally outraged and determined young men, and a traitor from within his own ranks—one who until almost the last moment is his most trusted lieutenant…

Between its aristocrats and its criminals, The Mysteries Of London is populated by a handful of respectable, middle-class (and mostly Scottish) characters, whose paths are crossed by Fergus in one or other of his various guises. Early on we find him pursuing the lovely Miss Mary Trevor, apparently because she reminds him of his lost love, Mary Macfarlane, even aside from the coincidence of their names. Mary is in love with poor but honest Frank Percival (poverty-stricken younger sons abound in this narrative, presumably as a criticism of the English system of primogeniture); but he is away, travelling on the Continent for reasons never explicated, when the Marquis de Rio Santo first enters Mary’s orbit. Between the “hypnotic” power of the Marquis’s personality and pressure from her family, Mary finds herself engaged to the Marquis almost without her volition. She still nurses Frank in her heart, however, until she is given reason to believe that he has been dallying with another woman even while making her impassioned declarations.

(The woman in question, the Marquis’s first romantic “victim”, is introduced to us rather marvellously as “Ophelia, Countess of Derby, the widow of a knight of the garter”, in the first but by no means the last demonstrations of Paul Féval’s complete failure to grasp the English system of title usage.)

Frank gets back to England to find himself supplanted by the Marquis, upon whom he forces a quarrel and a duel. A crack shot (of course), the Marquis shoots but refrains from killing Frank, who is left to suffer through a slow recovery under the care of his best friend and physician, Stephen Macnab.

And this is where things get complicated. (Yes, this.)

Stephen (whose surname is variously spelled Macnab, McNab and M’Nab throughout the text) is the son of a widowed mother—widowed when her husband was brutally killed many years before:

The death of his father, of which he had been the accidental witness, had at first shaken his youthful faculties; but he had soon recovered from the shock, and the lapse of years had now removed all the effects of the calamity upon his intellect. But the remembrance of his murdered father, and the image of his murderer, were engraved upon his mind in ineffaceable characters of blood. The assassin, whom he had seen for an instant, in consequence of the fall of his mask, was not stamped upon his memory with very certain indications: one circumstance, however, was still luminous—it was the form of a tall, robust, and supple man, with black eyebrows, knit together with a long scar drawn distinctly on his heated forehead. He saw all this as in a dream, but a burning fever for vengeance was kindled in his mind…

Staying with Stephen and his mother are Clara and Anna Macfarlane, the daughters of Mrs Macnab’s brother, Angus: a Scottish landowner and magistrate known generally as just as “the laird”. Mrs Macnab did – and, perhaps, does – have a second sibling, a sister called “Mary”…

When we are first introduced to Stephen, smug male that he is, he is hesitating between Clara and Anna, never doubting that he can have either for the asking; but although Anna is in fact in love with him, he only needs to realise that Clara is attracted to another man to become unalterably fixated upon her. This discovery occurs during a complicated scene in church, which finds a certain handsome stranger gazing fixedly at the young woman carrying around the collection plate, Clara Macfarlane palpitating over the handsome stranger, and Stephen toggling between homicidal fury and suicidal despair. (From the way the narrative unfolds we initially assume it is Mary Trevor who is carrying the plate, but it will very belatedly be confirmed as Anna Macfarlane: one of many missing subplots.) Later we learn that in his “Mr Edward” guise, Fergus has a house very near that in which the Macnabs live, and that Clara has become infatuated with him while watching him from the window. He, in turn, has distantly flirted with her, kissing his fingers at her and such, but without serious intention.

(People falling in love while spying on someone through their windows is a disturbingly recurrent theme in The Mysteries Of London, but since this very situation later leads to the rescue of Anna Macfarlane from the Earl of White Manor, we can’t entirely condemn it.)

So without knowing it, Frank Percival and Stephen Macnab have been supplanted by the same man. Stephen’s romantic sufferings recede while he is fighting to save his friend’s life, however, and he is distracted from them further by Frank’s feverish muttering when, it appears, he is the grip of a nightmare:

“The scar!” cried Percival suddenly; “did I not see the scar upon his forehead?”

Stephen had started up. “The scar!” exclaimed he; “oh! I remember!”

“Upon his red forehead!” rejoined Frank. “It appeared white and clearly defined.”

“From his left eyebrow to the upper part of his forehead?” said Stephen, involuntarily.

“From his left eyebrow to the upper part of his forehead!” repeated Percival.

“Frank!” cried Stephen; “you too know him then, In the name of Heaven, who is it you are speaking of?”

Frank did not reply; sleep had again overpowered him…

Stephen never gets to follow up the mystery of the man with the scar, because Frank’s life is still hanging in the balance when Clara and Anna Macfarlane disappear, which not unnaturally distracts him from all other considerations.

One of the numerous (not to say infinite) minor characters of The Mysteries Of London is a certain Mr Bishop, whose main profession is indicated by the usual rider which accompanies his name, “the burker”. Hilariously enough, in Paul Féval’s twisted vision of London, not only does Bishop deal openly in dead bodies, he keeps a showroom of his merchandise. Having failed to get any help from the police in the matter of his cousins’ disappearance, the desperate Stephen calls upon Bishop and asks to see what he has in stock:

All around this place—which occupied the space generally employed as kitchens and coal cellars in ordinary houses—were ranges of marble tables sloping forward.

It was a frightful spectacle, to see dead bodies lying there, stripped of their sere-clothes, symmetrically arranged with a view to being made an article of traffic…

The girls aren’t there, but as we know, Bishop is very well aware of the fate of one of them:

“Now then,” continued Bishop—Bob having shut the door—“what I have to tell you is—the devil take me if I tell you or any other man”—and he seemed embarrassed in speaking of it even to Bob—“I have never undertaken a business of this kind; but you, Bob, have neither heart nor soul, and provided you are well paid—”

“Shall I be well paid, Mr Bishop?”

“The matter in hand is, that—they want to carry off some young girl alive for the doctor to make some surgical experiments upon…”

Bishop is right about Bob, who almost at the same moment is approached by Paterson, the Earl of White Manor’s steward, who also has a proposition for him:

“You know that little girl in Cornhill?”

“Anna Macfarlane? I know, your honour; I was speaking about her only a minute ago to that gentleman who has just left.”

“She is a divinity, by Heaven!” exclaimed Paterson… “I am sure his lordship would be enraptured with the girl at first sight—we must have her.”

Thus Bob finds himself in something of a dilemma:

“What the devil shall I do?” said Bob, “it is dreadfully awkward: one hundred pounds from Bishop! two hundred from the steward! a very pretty sum. But the sweet girl cannot serve as a subject for Dr Moore, and a plaything for the earl at the same time—that’s very certain—that’s not possible. And yet I promised Bishop; I promised that leech, Paterson…”

…until it occurs to him that Anna has a sister, who will do quite as well for Dr Moore.

The sisters are lured away from home with a false message to meet their father at a certain public house, run by a couple who used to be in the Laird’s service, which lulls their suspicions. Unfortunately for the girls, the Gruffs are in league with Bishop, and they are not the first to disappear through a panel in the floor, to be lowered into a boat on the river below; although they are – perhaps – luckier in that they are only drugged, not dead.

To the mortification of the Gruffs, who should show up in the middle of these dark dealings but the Laird himself? – who catches a glimpse of his daughters being lowered through the floor. A desperate pursuit, an even more desperate battle with Bob Lantern, ends with the Laird being severely beaten and tossed into the river, while the stupefied girls are carried off to their separate fates…

While this (what we might call ‘Plot B’) is unfolding, over in Plot C we are hearing the history of Susannah and Ishmael Spencer. The significance of this is not revealed until much later in the story, when we get a flashback to Fergus’s return to Britain after his glorious career as a pirate, when he begins the construction of his revolutionary army. He and his angry Scottish offsider, Graham, call upon an even angrier Scot: Angus Macfarlane, who Fergus finds concocting plots to murder the Earl of White Manor, in vengeance for his (the earl’s) appalling treatment of his wife, the former Mary Macfarlane.

Fergus learns from Angus, among other things, that at the outset of the former’s piratical career, rumours abounded that he had returned to England, and that false sightings of him were frequently reported. Unfortunately for Mary, these happened to coincide with her pregnancy—leading White Manor (already regretting his marriage, and subject to fits of violent insanity at the best of times) to convince himself that her expected child was actually Fergus’s. When the girl was born he took her away from her mother and gave her up to the tender mercies of Ishmael Spencer; while as for Mary—oh, take THAT, Thomas Hardy!—

“Two days afterward he dragged his wife to Smithfield. Godfrey made her go into one of the sheep pens, which happened to be empty, and cried out loudly three times: ‘This woman is to be sold—sold for three shillings.’

“‘Let me pass,’ cried a man, ‘I wish to purchase, for three shillings, the Countess of White Manor.’

“The man was dressed in the coarse costume of a cattle dealer. Upon seeing him, Godfrey’s courage forsook him, and he made a movement to escape. Mary has never mentioned, in her letters, the name of this man, but when I went to London, public rumour informed me of it. It was the young Brian de Lancaster, the brother of the earl…”

As Angus broods over his bloody plans for White Manor, Fergus manages to re-channel his anger into his own cause, and recruits Angus as one of his lieutenants…

…but it is, in the end, Angus Macfarlane who betrays Fergus—not that we ever really understand what is going on in the feverish last section of the story, where the editing makes bewildering nonsense out of the inevitable long and convoluted explanation, with which such fiction necessarily closes.

Angus is rescued from the river after his attempt to rescue his daughters, and ends up in Fergus’s care. He is raving, near total insanity, and makes a very nearly successful attempt to murder Fergus. We get confirmation during this section that it was Fergus who killed Stephen’s father, and that Angus knows it; and has only refrained from revenging himself upon Fergus for the death of his brother-in-law because (i) Fergus is sort of his brother-in-law too, sharing his grief over Mary; and (ii) his hatred of the Earl of White Manor is his prevailing passion—at least until his daughters are abducted.

It is this that pushes Angus over the edge, understandably, though both girls are eventually rescued. The problem is—as the narrative stands, we never know why Angus is so sure that Fergus was behind the girls’ abduction. It was, of course, in Clara’s case, one of his co-conspirators who was behind it; but Angus seems to have more direct guilt in mind (though, at the same time, he cannot possibly believe Fergus had anything to do with Anna falling into White Manor’s clutches). Perhaps a cosmic irony was intended, with Fergus being taken down by the one crime he didn’t commit? In any event, it is on this basis, and just before Fergus is to set his revolution in motion, that Angus turns on him…

It is, however, Frank Percival and Stephen Macnab who directly intervene, making a citizens’ arrest of sorts. Stephen has his father’s death to avenge, and on the testimony of Angus knows who his killer was; now he gets proof for himself:

At that moment Rio Santo, who had succeeded in withdrawing himself from the maddening grasp of the laird, raised his head—his brilliant eye flashed fire—a reddening tinge proceeding from the efforts of Angus, or from anger, suffused the features of the marquis, till then so pallid; his brows were knit, and on the purpled skin of the forehead a livid scar appeared, extending from the eyebrow to the hair…

So much for Stephen; as for Frank—

“I have come to ask you, my lord,” replied Frank, hardly able to restrain his anger, “for an explanation of a cowardly and nameless crime.” He raised himself on the points of his toes, and whispered in the ear of the marquis, “I am the brother of Harriet Percival.”

“And the disappointed lover of Mary Trevor!” sarcastically added the marquis. “I declare to you, sir, that I had not the honour of your sister’s acquaintance.”

“That is true,” retorted Frank. “You killed her without knowing her.”

Him or anyone else! Of all the pieces of hack-handed editing in The Mysteries Of London, this one takes the cake. Some three hundred pages before this moment there is a single passing reference to “poor Harriet Percival”, and that is all we know about her. Fergus, meanwhile, is hardly more confused than we are: he tries to get an explanation out of Frank, but the situation takes an even more dramatic turn before he can give one, so this particular subplot is left hanging, a perpetual mystery.

Events then occur in a rush. Fergus is arrested, tried and convicted, not for his attempt to overthrow the government and assassinate the king, but for the murder of Mr Macnab (who had accidentally stumbled over an important secret, in the early days of Fergus’s plotting), and for being the mastermind behind a plot to rob the Bank of England—by tunnelling in from underneath!!

Good grief! – was this the earliest instance of that perpetually popular crime-plot??

Meanwhile, Clara, still in an extremely shaky condition of body and mind, finds out who it was she was infatuated with, the real identity of “Mr Edward”. In her unbalanced state, she makes her way to Newgate, and happens to be on the spot when Fergus is broken out by his still-loyal accomplices. She ends up being carried off by Fergus, who uses her presence to confuse the troops who are searching for a single man on a horse, and travels with him all the way to Scotland—to what should be her own home, Crewe Castle, Angus’s property (though bought for him by Fergus, to be used as a hideout if / when necessary).

And maybe I take it back about the Harriet Percival editing being the most confusing, because we are missing something important here, too—namely, the key to the working out of Fergus’s fate, wherein Clara becomes convinced that despite his engagement to Mary Trevor, her real rival for Fergus is Anna; and perhaps she’s right:

It was a singular journey. During the whole of it, he conducted himself toward Clara as a father would have done toward a beloved child. But, from the impression which had been produced upon him by the sight of Anna, when she presented to him the plate for his donation in Temple church, the marquis, in the strange and unconnected conversation which he had with Clara, several times inadvertently pronounced the name of her younger sister. Each time, that name fell as a heavy weight upon the heart of Clara…

From hints remaining in the text, we deduce that at some point Clara suffered a strange and tormenting dream, in which Anna came between her and Fergus, though we never know if this had any basis in reality. From Fergus’s reaction, almost certainly not:

“She is not there today,” she said, with joyful anxiety. “Tell me, Edward, she is not come, is she?”

Rio Santo saw at once that the poor girl was under the dominion of some strange hallucination; but he could not comprehend of whom she was speaking.

And poor Fergus is indeed fated to be taken down by the crimes he has not committed. Harriet Percival, nothing; it is the once-glimpsed Anna Macfarlane who dooms him:

“My father!” exclaimed Clara. “Oh, yes, yes, Edward! the farm is just on the other side of the hill. O! how happy we shall be there!”

She paused abruptly, but immediately afterward added: “That is to say, if my sister does not come, as she did the other time.”

A flash of ungovernable fury darted from her eyes. She suddenly threw herself back upon the ground, and her hand, by chance, fell upon the cold barrel of one of the pistols. Her action was rapid as thought itself. An explosion broke the silence of that sequestered spot; Rio Santo fell to the ground—the ball from the pistol had struck him in the breast…

Some time later, Fergus is found by quite another woman—the lonely occupant of Crewe Castle:

When the moon…rendered the spot visible by her silver light, a female form was seen kneeling by the unfortunate marquis. She was praying.

This was Mary Macfarlane, the Countess of White Manor. She had just recognised, in the dead body stretched upon the grass, Fergus O’Brian, her first, her only love…

Having reached this melodramatic conclusion, The Mysteries Of Paris wraps itself up with a few hilariously abrupt paragraphs—which serve the secondary purpose of illustrating how much of the narrative I have been obliged to ignore in this review, even in this severely cut-down version of the text:

Prince Demetrious Tolstoy was recalled to Russia in 1837.—He has in his old age become a hermit. The Viscount de Lantures Lucas was espoused to a Blue Stocking, and says—that he is now a most unhappy man. Bishop the Burker was hung for the murder of a child only six years old; Snail became a policeman; Rowley was sent to Botany Bay for experimenting upon an Irishman; Doctor Moore is now dead; Tyrrel the blind man is a banker, and chairman of a railway company, in Thames-street, and handles millions. The duchesse de Gevres, alias the Countess Cantaceuzini, has assumed the name of Randal, and has charge of Mr Tyrrel’s house; and Captain Paddy O’Chrane is now landlord of the King’s Arms.

Gilbert Paterson, on the night of Rio Santo’s escape from Newgate, was knocked down by a person on horseback, and a waggon passing at the moment, crushed him beneath its wheels. Bob Lantern is confined to St Luke’s Hospital, his wife Temperance sharing his fate, gin and rum having deprived her of her reason…