Thus he flatters and she believes, because she has a mind to believe; and thus by degrees he softens the listening Sylvia; swears his faith with sighs, and confirms it with his tears, which bedewed her fair bosom, as they fell from his bright dissembling eyes; and yet so well he dissembled, that he scarce knew himself that he did so: and such effects it wrought on Sylvia, that in spite of all her honour and vows engaged to Octavio, and horrid protestations never to receive again the fugitive to her arms, she suffers all he asks, gives herself up again to love, and is a second time undone…

So where was Aphra Behn between 1685 and 1687? Writing, of course. It was quite a good time to be a Tory writer, the very events that had so shaken the country opening up fertile ground for the monarchists. Behn had done her Tory duty early in 1685, producing an elegy for the departed Charles, and another for the widowed Catherine (who did a bunk back to Portugal as soon as she could organise it – and who can blame her?); although neither of these can hold a candle to the 800 line “pindarick” she wrote to celebrate the coronation of James. Around the same time, Roger L’Estrange received a knighthood and returned to his old position of Licensor Of The Press, John Dryden was confirmed as Poet Laureate – and Thomas Shadwell was blacklisted.

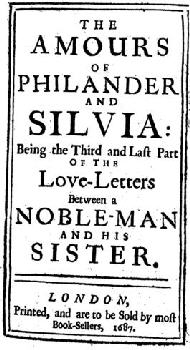

But for the most part the theatre was still stagnant; it was not until towards the end of his reign that James, all too late, began commissioning plays in the hope of using them to win some public support. Aphra Behn would not get another play produced until 1687, when both The Luckey Chance and The Emperor Of The Moon brought her dramatic success; the last of her lifetime. Also during 1687, Behn published the third part of her first venture into fiction as The Amours Of Philander And Sylvia. This is easily the longest of the three volumes, which may in part account for the delay in its appearance. It also finds Behn using a third different form of prose writing in as many volumes. While a few letters are interpolated, this work is worlds away from the epistolary style of the first, or even the “half-and-half” approach of the second, and presents as what we would now view as a conventional piece of third-person narration; although the narrator does make personal comments and additions from time to time, as we shall see.

This third volume is, I imagine, by far the most difficult for most modern readers to absorb. It consists of two overlapping yet distinct stories, the second being Behn’s account of the Monmouth Rebellion of June, 1685, in which her old friend Lord Grey suddenly reappeared on the public stage. It may even be that Behn had begun her third volume before that, then had to scrap it and start over when reality suddenly intervened. From the reader’s point of view, the difficulty here is that Behn not only describes the rebellion and its aftermath, but includes any amount of insulting minutiae about the Duke of Monmouth which, while it would have been perfectly familiar to a contemporary audience swamped by accounts of Monmouth’s life and death, means very little to the reader of today.

First, however, we rejoin our pairs of lovers. Sylvia has promised to marry Octavio (Brilliard notwithstanding) if he will take revenge on Philander for her, while Philander is still indulging in his dangerous affair with Calista, in spite of the growing suspicions of her husband, Clarineau, and Dormina, the servant set to spy upon her. Ironically, Clarineau’s way of showing his displeasure, namely, failing to visit Calista’s bed, which would have been more than welcome to her at any other time in their marriage, is now a matter of urgency: Calista is pregnant, but cannot bring about the encounter with her husband that she needs to cover her infidelity.

As her condition begins to show, Calista begs Philander to run away with her. This escapade finds Calista, too, in drag: a guise that brings out her (to Philander) strange resemblance to Octavio…and, perhaps, also makes clear the basis of her attraction for her lover:

I own I never saw anything so beautiful all over, from head to foot: and viewing her thus, (carrying my lanthorn all about her) but more especially her face, her wondrous, charming face—(pardon me, if I say, what does but look like flattery)—I never saw anything more resembling my dear Octavio, than the lovely Calista. Your very feature, your very smile and air; so that, if possible, that increased my adoration and esteem for her…

Remembering the fate of Clarineau’s first wife, both Philander and Calista carry weapons as they try to make their escape. They are caught by Clarineau, his nephew and his servants. As the latter engage Philander, Clarineau draws a poniard and stabs Calista, who fires her pistol at him, wounding him. Philander fights off the others, and manages to escape with the injured Calista. However, the two are soon caught and imprisoned – their jailers not realising Calista’s sex. She is terrified of being returned to Clarineau and his vengeance, while Philander knows that he himself will suffer nothing worse than a spell in prison and a fine for the cuckoldry. Calista having her jewels with her, Philander is able to pull his usual stunt – “The master of the prison was very civil and poor” – and Calista is allowed to escape, fleeing to Brussels and taking refuge in a convent where the Abbess is her aunt.

All this Philander recounts in a letter to Octavio, concluding with a request that Octavio write on his behalf to the magistrates of Cologne – sending to Sylvia at the same time another letter filled with the usual excuses. Having already broken his oath to Philander, Octavio shows her both. It doesn’t quite go as he expected. The outraged Sylvia insists upon travelling to Brussels, so that she can confront Calista – only to find herself so personally affected by Calista’s beauty (and, of course, by her resemblance to Octavio), that she almost finds it in herself to forgive her perfidious lover. Almost. On departing, Sylvia takes her revenge by giving to Calista the letter that Octavio gave to her; and Calista discovers that the man she believed loved her so honourably and tenderly has given a boastful, blow-by-blow account of their affair to another man…and that man her own brother. Sylvia, meanwhile, swears that she has cut Philander from her heart forever, and is entirely Octavio’s…

In her handling of the relationship between Sylvia and Octavio, and then again in the eventual reuniting of Sylvia and Philander, Aphra Behn displays a frank fascination with the masochistic potentiality of love – and an even greater one with the capacity of lovers for self-deception. Although we here a lot about “the brave, the generous, the amorous” Octavio, Behn’s language is belied by her action. Octavio’s obsession with Sylvia is an exercise in delusion and denial. To us, the onlookers, his passion for Sylvia is clearly a kind of physical addiction, a habit that he cannot kick, one that manifests as a total refusal to see reality.

When Brilliard hears of Sylvia’s promise to marry Octavio, he appeals to the local authorities, declaring himself her husband. Octavio is connected, however, and Brilliard’s attempt to claim his rights ends in failure. Although Octavio is at first horrified by Brilliard’s declaration, Sylvia manages to convince him that at the time she “married” Brilliard, he already had a wife and children, as she later discovered. At this time, Sylvia gives Octavio her own account of her relationship with Philander; and in an hilarious touch, Aphra Behn reveals that she and Sylvia were both readers of the London Gazette:

…but all search, all hue-and-cries were vain; at last, they put me into the weekly Gazette, describing me to the very features of my face, my hair, my breast, my stature…

The apparent barrier to their relationship removed, Octavio’s passion for Sylvia returns with redoubled force: “…he was given over to his wish of possessing of Sylvia, and could not live without her; he loved too much, and thought and considered too little…” Octavio renews his promises of marriage to Sylvia, and begins to lavish extravagant gifts upon her, his obsession with her growing uncontrollable…and in context, more than a little creepy.

Although his acquaintance with Sylvia begins when she is another man’s mistress, although he hears from both Philander and Sylvia the full truth of their relationship, Octavio insists upon courting Sylvia as if she were still the innocent girl she once was – not out of generosity, or kindness, or tact, but because this is the only way he can justify himself to himself. Sylvia is entranced by the fantasy world Octavio creates for them, which allows her to pretend that she has regained the position in life that she threw away for Philander, and intoxicated by her sense of power; she eagerly plays the part Octavio has tacitly written for her. When their mutual role-playing game ends, inevitably, in sex, Sylvia reacts not as an experienced woman, but like a ruined girl: “At first he found her weeping in his arms, raving on what she had inconsiderately done, and with her soft reproaches chiding her ravished lover…”

And perhaps here I should mention that while she lies in Octavio’s arms, weeping for an honour and a virginity long since departed, as Octavio swears to repair the great wrong he has done to her by making her his wife…Sylvia is at least five month’s pregnant with Philander’s child.

One of the most difficult things for modern readers to come to terms with in the literature of this period is its attitude to pregnancy, which is generally treated as just an inconvenience, a nuisance, but nothing that should be allowed to interfere with the business of life. It is certainly never considered a reason why two people shouldn’t have an affair. (If anything, on the contrary: you know the old saying…) In this respect, Love Letters is entirely representative. Remember that Calista, too, is pregnant when she finds refuge in the convent. There, taking stock, she is overwhelmed with shame and remorse. When her child is born, she has it taken away, before giving up the world and becoming a nun. Meanwhile, Sylvia also bears her baby…which is never mentioned again. We are given no hint of its fate; it simply disappears; and except for one or two passing references to Sylvia getting her figure back, there is no indication that she was ever pregnant, or that she ever thinks about it again. Nor is the double father remotely interested in his children’s fates.

Several decades after this, Daniel Defoe would be using his anti-heroines’ attititude to their children as a yardstick of their characters; here, Sylvia’s pregnancy is nothing more than a measure of the depth of Octavio’s delusion. As his obsession grows, Octavio rains money and jewels upon Sylvia, and sets her up in a mansion, swearing that he will marry her, “As soon as Sylvia should be delivered from that part of Philander, of which she was possessed.” But before Octavio can make good on his promise, Philander reappears on the scene…

Released from prison, Philander travels to Brussels, to the convent, where he hears quite a few home-truths from the Abbess before the door is slammed in his face. This encounter reveals to Philander that Octavio has betrayed him to Sylvia; and here Aphra Behn gives us another glimpse of the ugly reality of her world; woman’s world. Behn offers excuses for women’s perfidy in love, arguing that the world as it is hardly allows women to be honest if they would (and note the revealing slip into the first person):

Thus she spoke, without reminding that this most contemptible quality she herself was equally guilty of, though infinitely more excusable in her sex, there being a thousand little actions of their lives, liable to censure and reproach, which they would willingly excuse and colour over with little falsities; but in a man, whose most inconstant actions pass oftentimes for innocent gallantries, and to whom it is no infamy to own a thousand amours, but rather a glory to his fame and merit; I say, in him, (whom custom has favoured with an allowance to commit any vices and boast of it) it is not so brave.

But as with Behn’s railing against “interested” marriage and the selling of young girls to old men, this denouncing of the double standard is a cry in the wilderness. Despite Philander’s breaking of his vows to his wife, his seduction of Sylvia, and his months of bald-faced lies to her as he seduces and ruins another woman, we are given to understand that the only crime committed against honour in all this is Octavio’s breaking of his promise to Philander, the betrayal of man by man; that in fact, it is Philander who is the injured party:

…he no longer doubted, but that his confidante had betrayed him every way. He rails on false friendship, curses the Lady Abbess, himself, his fortune, and his birth; but finds it all in vain: nor was he so infinitely afflicted with the thought of the loss of Calista (because he had possessed her) as he was to find himself betrayed to her, and doubtless to Sylvia, by Octavio.

Philander and Octavio will later fight a duel on this point; later still, Octavio will concede to Philander that he was the one who committed the real breach of honour. And it is Octavio, the obsessive lover Octavio, who will finally put Woman firmly in her place – unearthing the novel’s subtext again in the process:

“These vows cannot hinder me from conserving entirely that friendship in my heart, which your good qualities and beauties at first sight engaged there, and esteeming you more than perhaps I ought to do; the man whom I must yet own my rival, and the undoer of my sister’s honour. But oh—no more of that; a friend is above a sister, or a mistress.” At this he hung down his eyes and sighed—

But Octavio still has some distance to travel before he can set aside his passion for Sylvia and become “a real man” – a man’s man, as it were. Although she has, to all appearances, got Octavio exactly where she wants him – has the prospect of a life so far beyond what she might expect in her circumstances as to almost boggle the mind – Sylvia is finally, fatally, betrayed by her vanity. Her absolute power over Octavio she credits to her own irresistible charm and beauty, not to Octavio’s consitutional blindness; and so abject is he in his devotion, she begins to take him just a little for granted…

Although Philander’s behaviour has killed her love for him, Sylvia realises that his betrayal of her, his finding another woman more beautiful, more desirable, than she, still rankles. She begins to toy with the notion of bringing him back to her feet, just to show that she can. As for Philander, Sylvia vanished from his thoughts the moment he set eyes on Calista; yet when he receives a letter from her declaring that she doesn’t want him any more, he instantly discovers that he wants her – and swears that he will have her again.

The resulting mutual exercise in emotionless manoeuvring and jockeying for the position of power evolves into a sick recapitulation of their original encounter – both of them falling back into their original roles without even recognising it (or as Behn puts it, “So well he dissembled, that he scarce knew himself that he did so…”) – and ends, sure enough, in Sylvia’s bed…where Octavio finds them. And even this he forgives…but in a seemingly contradictory yet psychologically convincing touch, this for Sylvia is the final straw. She has demonstrated the limitlessness of her power over Octavio; he no longer holds any challenge for her. Instead, bundling up the jewels and money and other portables that he has given her, Sylvia elopes again with Philander.

What follows is one of this novel’s strangest passages – indeed, one of the strangest things Behn ever wrote – as Octavio, his eyes opened at long last, retreats from the world as his sister did, entering a monastery. Here, the narration suddenly switches to the first person, as we hear that, I myself went to this ceremony, having, in all the time I lived in Flanders, never been so curious to see any such thing…

The evolution of the narrative voice across these three volumes is intriguing, and a fairly clear indication that initially Behn intended to write only the first of the three. The letters that make up Part 1, as you may remember, were supposed to have been found in a closet after Philander and Sylvia left the house where they had been living together between the time of their original elopement and Philander’s arrest, escape and flight from France. Presumably, then, the writer of the first volume’s preface is not the same person who supplies the narrative voice for the later ones. This third part contains some interesting experimentation with narrative possibilities, as Behn shifts back-and-forth between third-person-omniscient and first-person-onlooker – sometimes within the same passage.

Although she was not, as I have said, at all religious, Aphra Behn had a life-long fascination with the external aspects of Catholicism, its rituals, its art, its exoticism, its public display…all the things, in other words, that good Protestants were supposed to despise. There are various bits of erotica through this third volume of Behn’s story, but perversely, nothing that matches the sensuality of her description of Octavio’s withdrawal from the world:

For my part , I confess, I thought myself no longer on earth; and sure there is nothing gives an idea of real heaven, like a church all adorned with rare pictures, and the other ornaments of it, with whatever can charm the eyes; and music, and voices, to ravish the ear…But, for his face and eyes, I am not able to describe the charms that adorned them; no fancy, no imagination, can paint the beauties there: he looked indeed, as if he were made for heaven; no mortal ever had such grace… Ten thousand sighs, from all sides, were sent him, as he passed along, which, mixed with the soft music, made such a murmuring, as gentle breezes moving yielding boughs… All I could see around me, all I heard, was ravishing and heavenly; the scene of glory, and the dazzling altar… The Bishop turned and blessed him; and while an anthem was singing, Octavio, who was still kneeling, submitted his head to the hands of a Father, who, with a pair of scissors, cut off his delicate hair; at which a soft murmur of pity and grief filled the place…

As for Philander and Sylvia, they’re in pretty much the state you’d expect of two people held together only by their equal determination not to be the one who is discarded:

Philander, whose head was running on Calista, grudged every moment he was not about that affair, and grew as peevish as she; she recovers to new beauty, but he grows colder and colder by possession; love decayed, and ill humour increased: they grew uneasy on both sides, and not a day passed wherein they did not break into open and violent quarrels, upbraiding each other with those faults, which both wished that either would again commit, that they might be fairly rid of one another…

And from this state of mutual torment they are at long last delivered by a summons to Philander from Cesario: the rebellion of the Huguenots against the king of France is finally to take place…

[Aww, I really thought this would be the last of it. Curse you, Aphra Behn, and your infinitely discussable novel! Just one more piece, that’s all, I swear…]