Orlando, the amiable Orlando, returns then to Magdeburg, to his Isabella; and Oh! dreadful, dreadful recollection! demands her hand—compels her to meet him at the altar, and pledge those vows she cannot assent to.— Orlando, truly worthy, how sensible I am of your merit, and your love, but I cannot return it— Valentine, your still more happy brother, possesses it, and I am born to make you wretched.

One of my plans for this year was to participate in reading challenges as a way of bringing more obscure novels to light. This month, I had the chance to join in a very February-focused challenge, to read a book by someone called “Valentine”, or a book with the word “valentine” in the title. My choice was an anonymous novel from 1790 called Valentine.

What can I say? I have a very literal mind.

One of the stranger eruptions of the 18th-century was that of “sentimentalism”. This was a movement that went far beyond the merely “sentimental”: it was a reaction to the tenets of the Age of Reason; and far from celebrating rationality, it condemned it as an approach to life that encouraged self-interest and calculation; the worst kind of secularism. In contrast, sentimentalism saw emotion as a hotline to God. Man’s natural impulses and passions were, it argued, literally God-given, that is, everything that was pure, unselfish and generous, until corrupted by a wordly education. While the rational individual protected himself from harm by distance and a refusal to be involved, the sentimentalist opened himself to every emotion; and not only his own, but those of others with whom he came in contact, via an intensely cultivated empathy.

For all the age’s broad emphasis on rationalism, in artistic terms the first stirrings of this kind of deliberate emotional indulgence were evident quite early in the 18th century. We recall in Pamela, for example, Richardson’s staging of the reunion of Pamela and her father, which is organised to take place in the presence of the entire household, while everyone else stands around and watches them. The emotion of the two and the sentiments uttered by Mr Andrews upon learning of his daughter’s rise in the world are “feasted upon” by the gathered gentry, who analyse the scene afterwards as if they’d just watched a play. This vicarious pleasure in the extreme emotion of others is the key to the novel of sentimentalism, the model of which is Henry Mackenzie’s The Man Of Feeling. The novel’s naïve hero, Harley, travels around with all his nerve endings exposed, trying to help those in need, feeling every pain of every unfortunate he encounters, and being repeatedly taken advantage of by “rationalists”. He weeps, he suffers, he collapses and grows ill under the weight of his own emotion. In the end, discovering that the woman he loves, loves him, he dies of joy.

It seems incredible today, but The Man Of Feeling was an enormous success. People read it in groups for the specific purpose of crying over it publicly: to react in this way was a measure of a person’s “sensibility”. It’s not a spoiler for me to tell you that Harley dies. The very hallmark of the novel of sentimentalism is that almost everyone dies; the hero and/or heroine, certainly. Usually the final scenes leave just a person or two still standing, so that they can look back over the literary carnage and mourn. It is the strangest aspect of this very strange movement that it openly admits its inability to survive in the world of the rationalist; but to the sentimentalist, this very incapacity is evidence of an inherent moral superiority. They’re too good to live, you understand.

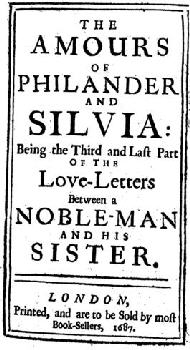

As always, other authors were swift to react to the emergence of a new subgenre; and for a couple of decades in the second half of the 18th century, tales of misery, death, doom and despair flooded the marketplace. Amongst this deluge was Valentine, a “pre-Minerva Press” novel – that is, it was published by William Lane before he introduced the Minerva Press imprint. I can’t say I’m exactly surprised to find Mr Lane cashing in on a trend.

One of the most interesting things about Valentine is its preface. This novel was, as I say, published anonymously, and I’ve been unable to decide in my own mind the sex of the author. The preface has a male persona, however, and the distance that its writer tries to put between – himself? herself? – and the text makes me suspect it was a man. Women writers at this time, whether publishing anonymously or not, were generally swift to reveal their gender as (hopefully) a way of warding off critical attack. On the other hand, a certain fixation upon the minutiae of dress in the story proper might suggest a woman.

In the preface, the writer tells us about being stood up by the friend he was supposed to having dinner with, and being instead left with a manuscript to read until the friend finally arrived, Which I was to give my candid opinion upon, on his return. As he found the manuscript, …worthy your notice, I send it unvarnished by any eulogium of mine, a tale unadorned by fiction. So he didn’t write it, and he didn’t find it, and anyway it’s not a work of fiction.

Typical of the genre, the preface is almost a novel of sentimentalism in itself. At completely unnecessary length, Mr I-Didn’t-Write-It tells us about his inheritance of a fortune, his retirement from business, his move to the country – and his belated discovery that, on the whole, he rather wishes he hadn’t retired from business and moved to the country:

A recluse and still life is not calculated to raise content, when the mind has been busily employed for years in a Court of Law. Man is born for society, the hours hang heavy when crowded with too much reflection; Books will not always entertain or relieve; there is a vacuity in solitude; to pass the tedious hours alone is burdensome, and I cannot solace the day by the sports of the field, which afford me no enjoyment…

And why is he so burdensomely alone? You have to ask?—

I have felt a severe affliction in my earliest days, by a disappointment in the tenderest of passions, that of Love!—Dear amiable woman! why was I fated to know you and to love you? Can I ever forget the innocence and beauty of your first appearance? No, never; never will the impression be effaced from my still bleeding heart. Love, early implanted, is not soon eradicated— I felt it in its full force, and could tell a very tender— But I am not addressing myself to you, for my own history, but to inform you that a few days past I was under an engagement to dine with a very particular friend…

Welcome to the world of the novel of sentimentalism, where explaining how you went to dinner with a friend will inevitably entail a recitation of the romantic woes that have scarred your life.

The story of Valentine takes place in 1745, during the War of the Austrian Succession, opening in the aftermath of the Battle of Sohr, which took place on the 30th September, and finishing after the Battle of Kesselsdorf on 15th December. Its sketched account of the relevant campaigns is, as far as some quick research can ascertain, accurate. This grounding in reality is rather unusual for this kind of novel. However, the setting isn’t all that important except so as to ensure a high body count amongst the male characters, every one of whom is a soldier.

But while the background of this novel is concrete, the plot is, far more typically, rudimentary. The children of the families of Dholte and Marluritz have been raised together. Count Marluritz literally wills his only surviving daughter, Isabella, to the older of the Dholte boys, Orlando. This engagement is ratified by Isabella’s brother, Ferdinand (just before he dies, too), and has royal approval. However, Isabella is in love with Orlando’s brother, Valentine, and he with her; the two finally declare their feelings for one another. As pressure mounts on Isabella to go through with the wedding to Orlando, Valentine convinces her to run away. He conceals her with a family he befriended after carrying the son wounded from the battlefield. They are noble, but the widowed Baroness has raised her two children far from the corruption of the Court. She confides to Valentine that Eleanor is not in fact her daughter, but a foundling who carried with her indications of a high birth. Valentine finally persuades Isabella to a secret marriage, but a call to arms separates them almost immediately…

Now, you could probably make a decent story out of this, but Valentine doesn’t even try. Instead it settles down into a competition to see which of its characters can behave and speak in the most unnecessarily extravagant manner – while remaining at all times blissfully unaware of its own absurdity. Therein lies the enduring charm of the genre. Indeed, Valentine is the most hilariously awful piece of tosh it’s been my pleasure to read in a long, long time. I giggled from the opening soliloquy of the hero, completely absorbed in his own romantic problems although up to his armpits in battlefield dead, to the inevitable body count in the final pages.

The novel is written in semi-epistolary style, alternating between letters between the characters and prose when straight narration is required. These interpolations have their own little chapter headings – for example, The Widow Woolstan’s Affecting And Pathetic Narrative, The Tale Of Woe Continued, Valentine’s Morn Of Happiness, and (since one “morn of happiness” is as much as any character in one of these stories is ever allowed) A Pathetic Conclusion.

Valentine himself sets the tone from the beginning, unable to refrain from dragging Isabella into everything he thinks, says or does. When we meet him he is soliloquising as he gazes around the body-strewn battlefield, his high-blown moralising on the empty glories of war rapidly and idiotically turning into a speech about how if Isabella doesn’t love him, then he wishes he hadn’t survived, either. He is interrupted in his self-pitying musings by a cry for help from a wounded soldier. This, naturally, brings on another soliloquy about how Isabella doesn’t love him, so really, what’s the point?—

“Can compassion be extended,” said he, “amidst this scene? I will assist thee, perhaps thou hast an Isabella who may mourn thy loss, may sooth thy pains. These wounds were gained in the field of honour; thy plaintive fair too may even now be weeping for thy loss; while mine, insensible and regardless of my life or fame, gives all her anxious cares and fears to her Orlando. Distraction’s in the thought, but I will assist thy enfeebled strength.” When looking around he beheld a youth wallowing in blood…

It must be said, some of the fun goes out of Valentine once its lovers come to an understanding, and Valentine stops being compelled to drag Isabella and her supposed cruelty into every single random thought that crosses his mind. On the other hand, this plot thread does climax in a passage that is a masterpiece of incoherency, when upon placing Isabella with the Baroness and her family, Valentine begins to worry that his friend Woolstan might prove a romantic threat; while at the same time he remains oblivious to Eleanor’s attraction to himself:

They parted, inviolable secrecy was promised by all parties—Isabella sighed, Eleanor sighed—the eyes of Eleanor followed him ’till out of sight. Eleanor loved Valentine better than any man on earth, Woolstan excepted, but Woolstan was her brother. Valentine left Isabella in safety, yet Woolstan was young, was susceptible! Isabella attractive! But Woolstan, bred with Eleanor from their infancy, must love her in preference to all the sex, and Eleanor is not Woolstan’s sister.

Since story is a minor consideration here, we can amuse ourselves instead spotting the various tropes of sentimentalism. Some of them are stylistic, like the insistence of the characters upon addressing each other by their names instead of ever using pronouns, and the use of archaicisms (“Dost thou, Isabella, truly intend such cruelty to Valentine?”) Others are philosophical, like the constant harping upon the superiority of the cottage over the court, the country over the city; a belief that here takes the author to such extremes, he feels compelled to insist upon the natural elevation of every aspect, every single action, of country life…even knocking on the door:

No burnished knocker graced the portal of the cottage door—no party coloured lackies with leaded canes preceded on before the carriage, and by their thundering reiterating rap, told their master of their errand.—These were not wanting here to grace the entry of Valentine at Staudentz, ever expected, ever welcome.

His whip performed the necessary notice, two taps, gentle as the breathing bosom of the lovely Isabella…

Mind you, the author’s determination to extol “simplicity” at every opportunity sometimes causes certain difficulties, such as when it clashes with a desire to bestow everyone with enormous fortunes (various solemn descriptions of death are interrupted to tell us who inherited what), or to to paint lengthy word-pictures of Isabella and her “elegant” wardrobe:

The beautious form of Isabella, which required no ornament, was nevertheless elegantly dressed; her robe, of white muslin (according to the fashion of the country) was long, but not tuck’d up, for the convenience of walking, covered with an azure coloured petticoat; round her waist was a zone, or cestus, of black velvet, fastened with a gold buckle, on her head was a bonnet, originally the manufacture of Leghorn, decorated with white ribbon…

Eleanor’s whole attention was fixed on her diamond clasps, her gold buckle, and the flowing elegance of her robe… She viewed Isabella as a Deity; while, on the contrary, Isabella beheld Eleanor as a model of perfection, luxuriantly adorned by nature! for Isabella was truly insensible to the power of her own attraction—and for dress, she subscribed to it more from custom than any intention she had to embellish those charms, in which nature had been so lavish to her…

Another idiocy here, one that to be fair is quite common in epistolary novels generally, is the author’s inability to give us the characters’ back-stories without having them tell each other at length things they must already know. Here the main culprit is Isabella, writing to her friend Bertha; the tone of their correspondence is entirely set by the opening paragraph of its opening letter:

And will Bertha still favor with her friendship the unfortunate, the unhappy Isabella? Will the daughter of the amiable Baroness Waesneri, still give sanction to her friend, removed from her to a distant home? Will she honor with her confidence the former partner of her heart, intrust her secrets, tell her inquietudes, pour the torturing anxieties of disappointment or expectation into her faithful bosom; and receive, in exchange, the heart rending troubles and distresses of her Isabella? Yes, you have told me you will…

At one point, Bertha addresses Isabella as, The friend of my infant, as well as my maturer years. Heaven knows what the two of them were talking about all that time: in an earlier letter, Isabella states, That Isabella is the daughter and only surviving child of Field Marshall General Count Marluritz, is all my Bertha knows of a life, young and already seasoned in the disappointments of this world’s glories… – before proceeding to edify her (and, of course, us) with her life story.

I’m sure it won’t come as any surprise to anyone to learn that Isabella is a crier. Well – that is to say – they’re all criers; that goes without saying; but Isabella takes the prize. Here are just a few, a very few examples of how she seems to pass most of her time:

At the mention of his name her eyes were suffused in a briny torrent…

I weep, Bertha—an involuntary flood of tears comes to my relief.— You will, at parting from the Baron Schwerin, let fall regretting tears; yet not with such poignancy of sorrow as these which fall so abundantly, so incessantly, from the eyes of Isabella…

“No, Valentine, I love but you alone. I cry incessantly, it is Valentine draws the tears…” I threw myself on my knees, and with a flood of tears eased the bursting heart of Isabella…

The letter however from the first friend of Isabella drew those crystal drops that were wont to fall from her eyes…

Isabella’s tears ceased not to flow, and more, for Valentine was now her husband, she need not now conceal the cause…

“…yet Valentine I waked in tears, and the pillow which supported the head of your weary Isabella, was wet with the gushing suffusion…”

And really, I can only say with Oscar Wilde— Anyone who doesn’t find Isabella’s relentless and determined misery quite hilarious must have a heart of stone.

However, perhaps the single outstanding quality of the novel of sentimentalism is the gap that develops between the reader’s perception of the characters’ actions, and that of the characters themselves; a gap that, granted, may have been a great deal smaller, or even non-existent, in 1790. These days, however, it is impossible not to be struck by the way in which the characters in novels like these view everything through the distorting lens of their own total self-absorption.

In Valentine, the best example of this is the sneaking behaviour of our putative hero after his hiding of Isabella. An increasingly frantic Orlando begins to suspect every man he knows of being responsible for Isabella’s disappearance – well, except for his noble and honourable brother – and finally challenges one of them, Baron Schwerin, to a duel. Does even this cause Valentine, who has looked on silently at his brother’s growing distraction, to confess himself responsible? Of course not. Instead, he lets his brother and his good friend go off and try to kill each other – as they very nearly do. In fact, it is evident during the duel that Orlando has stopped caring whether he lives or dies, and it is only due to Schwerin’s generosity that he escapes with his life. Even Isabella, more than a little self-absorbed herself, is disturbed by this event – although it is only the danger to Orlando to which she reacts. Her lover’s self-serving passivity doesn’t seem to bother her, nor that the man her best friend loves could have been killed just to preserve her secret. I guess that things like that are all in a day’s work, when you’re a sentimentalist.

Anyway…it all ends in tears, of course. Valentine has a double-barrelled ending, its final miseries described first in a letter from Schwerin to Bertha, and then again by the author in the third person; I suppose in case we hadn’t all suffered enough the first time. And since we’ve been studying the various lengths and forms of the run-on sentence, it pleases me enormously to be able to report that Valentine ends with one even longer than that which opened Rosabella…which of course gives me an excuse to wrap up this nonsense by quoting it:

Orlando left the chief of his fortune to Eleanor, which with her own, made it very considerable; they were at a proper time married in Berlin, and though it was not possible for a man to be more attached to beauty, than the Baron was to his lovely Eleanor, with whom he had been brought up from their tenderest infancy, yet had she not influence sufficient over him to make him quit the path of fame and glory, in which his father and all his progenitors had trod, a path of fame, although so unhappily fatal to his dearest friends, in the lamented, the valiant and brave Valentine with the amiable Isabella.